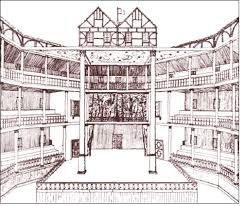

Why do we watch TV, movies, or plays? Why do we read (for pleasure)? Why do we play video games? In short, why do we consume stories? The obvious answer: it’s enjoyable. An idealist answer: it’s an escape. A scientific answer: beyond exciting the Broca and Wernicke areas of the cerebral cortex, stories engage the entire brain, expanding our creative and cognitive potential. The cynical answer: it is a way to “spend time.” Let’s scratch off the lackluster obvious example, and leave the cynical one for a moment, and focus on the idealist and scientist. Stories (in whatever medium) are an engagement and an escape from our world, our lives. We engage in stories to remove ourselves from “the pangs of despised love” and the “fardels bear[ing], to grunt and sweat under a weary life,” while at the same time we read and watch to better relate to and understand such slings and arrows. We could place these objectives on all of Shakespeare’s plays, but As You Like It fulfills a more meta role. The play itself acts as an engagement with the nature of stories, as I hope to demonstrate. As You Like It is very dividing; some people (for transparency sake, myself included) place it toward the top of their lists for favourite play, while others hate it. I believe this divide arises from the play’s lack of plot. Very little happens in this play: even less between Act I and the final scene. As You Like It may rival Hamlet for the most inactive play, but unlike the latter, this play does not centre on the inward conflict of a central character. The play lingers, as we meander from one conversation to another, we receive witty homilies on the Big Themes (Time, Nature, Love &c.) At times, this play reads more like a Platonic dialogue than a work for the stage. This becomes more evident when you contrast this play to its closest predecessors: Much Ado About Nothing, with its redundant “plots,” Henry V with its many battles, and Julius Caesar (although some sources put this after As You Like It). Shakespeare turns away from conspiracy and plots to the pastoral, where men wander and talk. And we sit and watch, or sit and read: we think, we escape, and upon reflection, we are keenly aware that we are participating in the act of story. The lack of motion is intentional: it slowly lures us in before we know it. The play opens with the protagonist, Orlando. He is kind, stronger than any man and lioness, and quite naïve. Even Adam, the family servant, can’t figure him out, asking: Why are you virtuous? why do people love you? In the opening scene, we learn about Orlando’s central problem: one that serves as a roadmap to the play. OLIVER Orlando has no opportunity for growth. He is in the prime of his life, and cannot make or mar because his brother is keeping him in idleness. At a time when so many young adults are coming out of school to find minimal opportunities, we can look back on Orlando’s struggles and relate. Sometimes we stress out about money, relationships, or the plethora of worldly problems—but sometimes we just want to do something meaningful. This is Orlando’s problem at the start. And this is not simply a comic problem, a representation of the Aristotelian “ridiculous”, but rather Shakespeare is in line with our current reality. In Hamlet, we witness the desire for suicide brought on by depression, and the internal psychological struggle it creates. In Orlando, we see the precursor to this maturity. Orlando is, in every way, far more rash than Hamlet. He has the youthful spirit of Romeo, but the state of Hamlet. He does not desire that his “too too solid flesh would melt” but seeks out death to end his suffering. It is a great tragedy that, today, there is a positive correlation between youth unemployment and suicide, and as we escape into our own Forest of Ardens (or stories) we cannot lose sight of this Orlando. Orlando is not killed by the wrestler, Charles, as both he and his brother desired. But when he returns home, he does not return to his life of idleness. His brother, hating him for no other reason than Orlando is a better person, decides to set fire to his cabin while he is asleep. Adam warns Orlando, and the two escape into the Forest of Arden. Out of duty, Adam is willing to die to help Orlando. Master, go on, and I will follow thee, Orlando flees from death, Adam to death: both needing to remove themselves from their own stories.  While this is happening, we meet Rosalind. Rosalind’s problem aligns with what we might expect from drama. Her father, Duke Senior, was not killed like many fathers in Shakespeare, but he was exiled by his brother. Rosalind is living with her uncle, the one who exiled her father, because her cousin, Celia, insisted on it. Celia is a character who loves to play the game “anything you have I have too”, which places her in the annoying little sister role which she plays well. ROSALIND Dear Celia, I show more mirth than I am mistress of; and would you yet I were merrier? Unless you could teach me to forget a banished father, you must not learn me how to remember any extraordinary pleasure. CELIA Herein I see thou lovest me not with the full weight that I love thee. If my uncle, thy banished father, had banished thy uncle, the duke my father, so thou hadst been still with me, I could have taught my love to take thy father for mine: so wouldst thou, if the truth of thy love to me were so righteously tempered as mine is to thee. (I.ii) After the wrestling match, at which Rosalind falls in love with Orlando, the new Duke banishes Rosalind, for no other reason than he hates her. And of course, if Rosalind is going to run away, Celia goes too. Rosalind disguises herself as a man, Ganymede, to protect them. So naturally Celia disguises herself too, as Aliena. Cajoling their fool, Touchstone, to go with them, they flee to the Forest of Arden to, according to Celia, find Rosalind’s father. They do go to the forest, but they don’t bother to find the Duke. Act II opens with both our introduction to Duke Senior and the Forest of Arden. And before I continue, I think this is a fair time to travel on a tangent about Shakespeare’s locations.  Renaissance theatre was minimalistic when it came to setting. The Globe offered some interesting aspects due to its levels and the cosmos depicted around the ceiling. However, the specifics of where a play took place could not be well replicated on the Renaissance stage, as Shakespeare famously bemoans in his prologue to Henry V. The history plays all take place in and around England, so the plays are rooted in those locations. The tragedies all draw on some historic context as well, so where the play takes place has an impact on the action. This is not so much the case with the more domestic comedies. Unless a fan of “Kiss Me Kate,” who knows where Taming of the Shrew takes place? Measure for Measure is set in Vienna, but a Vienna that strikingly resembles London. In Twelfth Night, he abandons the whole idea and sets it in the fictitious island of Illyria. Arden is interesting. There is an article here that traces the real Forest of Arden: an old forest not far off from where Shakespeare grew up in Warwickshire. Meanwhile, there is also a Forest of Ardenne in France, where Act I takes place. Marjorie Garber, in Shakespeare After All, takes a structuralist view and looks at the name itself: Arden. Arcadia/Eden. Arcadia, by 1600, was a well-established pastoral landscape, and of course, Eden refers to the garden. Garber’s theory is well reinforced in the play: the pastoral life is constantly lauded by the shepherd, Corin, as well as by Jaques: the melancholy courtier who falls in love with the pastoral life; while Duke Senior’s first speech links Arden to a prelapsarian paradise. This is certainly a fortunate combination, and maybe whoever named the real Forest of Arden picked up on this as well. Shakespeare, growing up in the forest’s shadow, had plenty of time to make this connection before writing As You Like It. So why set the court in France, when the forest is an ambiguous French/English landscape? The court is both a place of sinister plots and fops—when criticizing or lampooning court life, Shakespeare liked to use other nations, particularly the French. He is participating in the long tradition of denigrating the French. It is a common belief that the name Jaques would not be pronounced as a modern reader with even a limited understanding of French would pronounce it, but rather how it reads phonetically to an English reader (Ja-kw-es). Whatever belief you subscribe to when it comes to the naming of Arden, the important point is that Arden, more than other Shakespearean locations, is layered. In its naming, and also how the characters view it.

And the base setting as compared to the court, as Touchstone relates every time he matches his wits with one of Arden’s natives (mainly Corin and Audrey). Sometimes Arden is called a forest, other times a desert, depending on the speaker’s mood. In short, Arden possesses a personality because it is the reflection of a myriad of personalities. But mostly, Arden is idleness. Orlando’s frustrations at the start of the play comes from his idleness, his inability to make (or mar) anything. “Are not these woods/More free from peril than the envious court?” Duke Senior asks: the woods are free from everything. The peril of court, the change of seasons to icy winter—and yet, the flip side to that is that the woods are free of all that is good. There are two types of idleness: that which is forced upon us by circumstance and that which we choose. Sometimes, when I am feeling stressed as a result of “idleness”—or the lack of momentum—I seek comfort in reading, watching Netflix, or playing a video game. Are these not idle acts? I am escaping idleness with idleness. Rosalind and Celia go into the forest to find Rosalind’s father, but the first thing they do is buy a cottage: why? Corin, the old shepherd, works the cottage but does not have access to his flock. The goods belong to a churlish master, whose lack of care has bankrupted the estate. Rosalind offers to give Corin the money to buy the property, thus improving his lot. Celia quickly follows with: I like this place. Is this charity, or the pursuit of idleness? Why confront your problems if you can hide out in your own forest? The Duke and his men could have challenged his brother. Orlando could have sought the Duke’s help in attacking Oliver. Rosalind could have reunited with her father. All this would have advanced a plot: no one had any interest in doing so. So the Duke’s men turn to singing and hunting, Rosalind and Celia buy a cottage, and Orlando wanders the woods posting love notes on trees to his beloved Rosalind. I’m about 2,300 words into this thing and I haven’t mentioned the love story, which is the crux of this play! Probably because the love story is as inconsequential as the “All the World’s a Stage” speech which occurs towards the middle of the play. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a great speech: here it is in my terrible rendering.

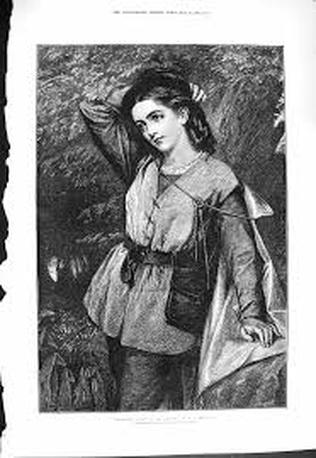

But the love story. Orlando loves Rosalind, Rosalind loves Orlando. As Ganymede, Rosalind has many private conversations with Orlando, at which point she could have revealed her true identity. There is no further impediment to their love. No warring families (Romeo and Juliet), no vow of celibacy (Love’s Labour’s Lost), no mismatched lovers (A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Twelfth Night), no pride getting in the way (Much Ado About Nothing). The only thing stopping their love is Rosalind’s idleness, and her insecurity. She needs to know that Orlando truly loves her, and so she tests him. Orlando is to woo Ganymede as if he were Rosalind. Through this test, Rosalind will determine whether Orlando loves her, and we get to luxuriate in a fine discourse on Love. What makes Rosalind fantastic is that she possesses the wit and power that ordinary women were not allowed to possess. Of course, she can only do this as Ganymede in the forest. That is why I believe the reconciliation and marriage that the comedic genre demands is as unsettled in this play as in the later “problem plays”. HYMEN Sometimes we can get caught up in our idleness, drown ourselves in stories to escape or understand. It is good to always try to advance our plot, and temper our idleness. To be comfortable, but not too much to hinder us from bettering ourselves. But when we come out of it, shouldn’t we try come out on top? Does Rosalind gain anything through her marriage? Was her only goal to get Orlando? Can she still be Ganymede in her father’s court? As the characters dance at the end of the play, we become painfully aware that, as much as we enjoyed watching or reading the play, we have to head back into the world – embracing the good and the bad, and all the rest.

2 Comments

Alex Benarzi

7/13/2022 04:22:50 pm

Thank you!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed