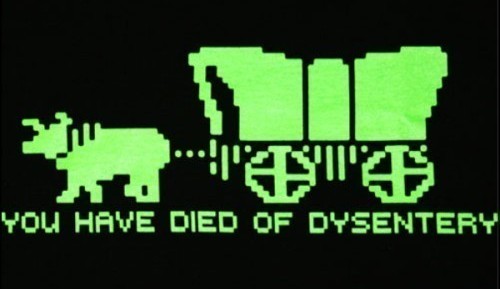

That being said, 1 Henry VI presents an interesting question in relation to its chronology. It might be Shakespeare's fanfare: his first march onto the stage. Or, it may have been presented after 3 Henry VI. If the first option is true, this play is a stand-alone piece, much like the original Star Wars in the context of the original trilogy. If the second option is true, this play acts more like the Star Wars prequels - which may account for the quality of the play. How you place the play in chronology will affect how you read the play. If it is the original work, the focus will be on the major plotline - the conclusion of the 100 Years' War between England and France. If you are viewing this as a pale reflection of the two superior plays - 2 Henry VI, and 3 Henry VI - the focus is on the War of the Roses, the main subject matter of the other two plays. If you subscribe to the first option, 1 Henry VI shows us how the War of the Roses began and coats this dark period in the glory of English victory (sort of) over the French. However, if the play is a prequel, we are watching the final breath of a great monarchy, and we already know how it ends. Yet, however you choose to read this play, it is a celebration in over exaggerated form of the glorious English against the corrupt French. On the surface, this is a very patriotic play about a somewhat recent time in English history. The trilogy itself is about the War of the Roses, a time in which none of the English nobility come out looking good. But the War of the Roses takes a backseat in this play to the conflict between England and France, or more specifically, the glorious English John Talbot against the evil Joan of Arc (or Pucelle). The first scene sets the two-fold tone of the play. We open with the funeral march of Henry V, the great warrior, great Christian, great monarch who does not suffer the blemish of usurpation that his father did, or the weakness of his son. Hung be the heavens with black, yield day to night! This oration is very reminiscent of the lamentations of the great heroes in ancient Greek drama. The metaphorical ghost of Henry V lingers throughout the entire play, to underscore how much of a failure everyone else compared to him. Again, we are dealing with a patriotic play, so the ineffectiveness of the parties involved in the War of the Roses has to be offset by the one great ruler leading up to the formation of Queen Elizabeth’s house, the Tudors. The other lasting trope we get in this scene is the idea of French magic. Obviously the villainous French were not strong enough to defeat the great King Henry V in any form of legitimate combat. They had to resort to conjurers and sorcerers, those un-Christian devils, to take him down. Shakespeare was often liberal with history, so this is not surprising. Also, Henry V did die suddenly, just not by magic. He suffered a fate that anyone who has played the old game Oregon Trail would be familiar with. Beyond the virtuous English combatting the devilish French, we are also presented with an intellectual debate throughout the play. At the end of Act I, Joan gains a decisive victory over Talbot when she defeats him at Orleans and claims the city for the French. The French celebrate by getting drunk and passing out. Talbot does not receive blame for his failure, and he does not lose the trust of his men. They immediately regroup and take advantage of the Frenchmen’s incapacitation, with Talbot at the lead. BEDFORD They sneak into the city and surprise the French, scattering their soldiers. The French commanders, instead of regrouping or planning, play the blame game, accusing the others of not doing their duties. Even the Dauphin joins in, accusing Joan of being a traitor. Joan alone has the good enough sense to stop this quarrel and suggest a plan, but as soon as she does, an English solider runs into their camp screaming Talbot’s name, and they flee. Soldier Not only are the French cowards for running, but unintelligent for falling for such a trick. Joan Pucelle is thought to possess magic, to grow beyond her maidenhood based on the fear that her name inspires. But in this play, Shakespeare gives Talbot that quality. Then there is the slightly out of place scene that breaks up the action in Act II: the only purpose of which is to show how wily Talbot is and how easily deceived the French are. The Countess of Auvergne sets, what she believes to be, a marvelous trap.

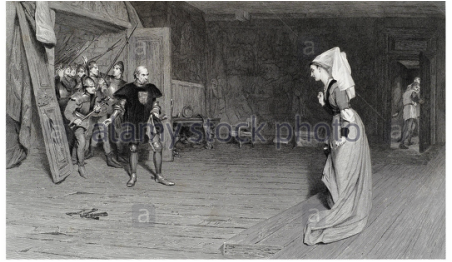

TALBOT Some people point to scenes like this to demonstrate Shakespeare’s amateur skills as a playwright, and it is poorly constructed. The plot is not well laid, the turn is too rapid, and the Countess is immediately contrite. It’s hard to see this as anything but cartoonish. Moreover, it demonstrates that the French are not only incapable of winning in honourable battles that they have to resort to magic, but they cannot win in underhanded seduction plots either. After a bit more back and forth between the French and English, we get to the end of Act IV and the death of John Talbot. History, not always conforming to theatre’s whims, suggests that Talbot died in battle in 1453, most likely struck down by a French solider. This propagandist play could not give the French the honour of killing the hero, so instead it is grief that takes down Talbot. His son joins the battle for the sole purpose of dying. When he is cut down by the French and his body is brought before Talbot, he laments. Thou antic death, which laugh'st us here to scorn, To top it off, a few lines later, the Bastard of Orleans suggests that they hack the bodies of the two Talbots to pieces, although his plan is dismissed by Charles. The thought of hacking up their bodies is too brutal even for the cowardly, witch-loving French Dauphin. The denouement wraps up this stand-alone play somewhat neatly. Charles thinks that, given Talbot’s death and revolts in Paris, he will be secure as leader of the French, but the English quickly regain their power and Charles swears his loyalty to King Henry in a turnaround as quick as the Countess’ to Talbot. Meanwhile, Joan is captured by the English and in a last act of propaganda, she is stripped of her maidenhood when she claims to have slept with every French commander. Also, we see her try to conjure spirits, giving truth to the claims of her being a witch, but even the spirits reject her. The Maid of Orleans reduced to ridicule and disgust – because that’s the type of play this is, and we have to appease the great Elizabeth I. Long live the Queen! The last scene muddies the waters just a bit. The end of Star Wars is the famous scene where the heroes who helped destroy the Death Star all receive medals to the tune of one of the greatest film scores. Given everything in this play, 1 Henry VI should have ended with a victory speech: the French have been subdued and their witch burned. But it doesn’t. The last scene involves Suffolk convincing King Henry to forget about his intended bride, kin to Charles, who will bring a large dowry and secure the friendship between England and France, in favour of Margaret of Anjou. Historically, this is one of the big moments in the War of the Roses, and leads to a series of conflicts not fully explored in the tetralogy. The play ends ominously with Suffolk’s triumph. Thus Suffolk hath prevail'd; and thus he goes, This may suggest that the sequels (2 Henry VI and 3 Henry VI) were already in the works. Or, it shows that in the midst of the great English propaganda there is a tragedy lurking and that the audience watching this for the first time – with full knowledge of the history behind the play – should not be so complacent. The French may not be a worthy opponent – but the English are England’s deadliest foes. This ending is unusual in Shakespeare’s cannon: things are often better tied up. However, the questioning of England’s prosperity and stability is something we see over and over again in the works. Next time: The War of the RosesOne of the detours that this play takes is to establish the War of the Roses, in the least dramatic way. York and Somerset have an argument about birthright, and during the argument pluck roses - York plucks a white rose and Somerset a red rose. The other nobles join the argument by plucking roses depending on whom they agree with. It is symbolism that beats you over the head.

This scene is purely for the benefit of the larger tetrology and so I will return to it when I cover 2 Henry VI and 3 Henry VI.

1 Comment

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed