Still, many are willing to support his political endeavours based on his past actions, rather than what he says. The opposing side, with a louder voice in the nation, does what it can to oppose his political career. The man decides that he does not like the political customs of the nation and acts contrary to them: many still support him. However, after some severe blunders during his campaign, which his opposition pounce on and drill into the populous, all turn against him. Even his once supporters distance themselves from him….. So, I may be fishing a bit, but read Coriolanus and tell me that the above summary does not accurately reflect both Coriolanus and Donald J. Trump. Look at one officer’s assessment of Coriolanus: Faith, there had been many great men that have How many times has Trump said or shown that he speaks his mind without a care for the political game that others play. He does not do political correctness. Throughout his play, Coriolanus portrays himself, and acts, as the lone wolf, to a fantastical degree. It is true. He went into Corioli alone and took out an army. His actions mirror what Donald Trump perceives himself to be. In his speech to the RNC, he said “Nobody knows the system better than me, which is why I alone can fix it.” So I read through Coriolanus again (which is not easy considering that this play ranks towards the bottom for me) and annotated it with many parallels between Coriolanus and Donald Trump. I thought that would make an interesting piece. But when the comparisons started jumping out at me, I knew that they had jumped out at others. A quick Google search of “Coriolanus, Donald Trump” confirms that this area has been tackled in blogs similar to mine to the L.A Times. Even before Trump entered the political sphere, Coriolanus-modern politician comparisons were made by many in the media. This same Google search taught me that the dystopian president from the successful Hunger Games series is named Coriolanus (I am certain this is deliberate.) So much for my brilliance. Here is what I am not going to do. I am not going to support or defame any politician, Trump included. And I am not going to suggest how Shakespeare predicted the future of our modern political theatre by creating characters like Coriolanus. The truth is that Shakespeare cannot be credited with the creation of Coriolanus. He was real, as were most of the characters in Shakespeare’s histories and the four Roman tragedies (Titus Andronicus, Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, Coriolanus). But what really separates Coriolanus from some of his counterparts is how much Shakespeare kept from his source material. Brutus, in Julius Caesar is not the Brutus we find in Plutarch (Shakespeare’s source for the character), with the exception of the accepted historical actions. Henry V, in his play, deviates from history, as does most of the characters in the York tetralogy. Shakespeare infuses these characters with dramatic and philosophic life that exceeds the lives that most people lead. But if you read the section on Coriolanus in Plutarch (again, Shakespeare’s source) it is quite dramatic. Granted, Plutarch may have had a flair for the dramatic himself, but because he is our best link to the real Coriolanus, we have to accept him to a certain degree. Someone who features prominently in Plutarch’s section on Coriolanus is Volumnia, Coriolanus’ mother. She is also, in my opinion, the best part of Shakespeare’s play. Take this brilliant line: Hear me profess

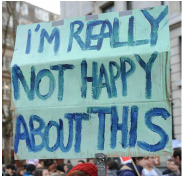

I’m off on a tangent. What does any of this have to do with Trump? Am I just shoehorning current popular figures in a hopeless attempt to drive traffic to my site? Maybe. But here’s my point. Shakespeare did not create Coriolanus. Coriolanus as Shakespeare presents him was real. Meaning, that for all the posturing that the myopic media does about how different Trump is in the political game, Trumps have existed as far back as early Rome (Coriolanus takes place around 491BC.) So talking about how Shakespeare invented Trump in the same way he invented the modern existentialist (through Hamlet) is a nonstarter. Instead, let’s use Coriolanus (as we find him in Shakespeare’s play) and Donald Trump as models to show how people are attracted to such magnetic leaders and, quickly after, delight in their destruction. Coriolanus to a certain extent is the same, but here Shakespeare is playing with the idea more deliberately. Furthermore, there are a few parts, where he gives us more insight into the “common people” than we get in his previous plays. In the opening of Julius Caesar, Flavius and Marullus – Tribunes, and “betters” to the commoners – come to scold a group of men for taking the day off work when they were not supposed to. The commoners don’t put up any resistance, except for some subpar wit from a cobbler. They leave, and Flavius says: “They vanish tongue-tied in their guiltiness” (I.i). Not only does the mob immediately disperse, but they were initially gathered to see a triumphant Julius Caesar. Throughout Julius Caesar, as the mob shifts their loyalties from Caesar, to Brutus, to Antony, they are singularly desperate for a leader to tell them what to do. What do these people want from their leader? We don’t really know, beyond the basic security and preservation of the state. In Julius Caesar the people are the placated masses, only good to make the stage look more crowded. They also allow Shakespeare a good line about killing poets, but that’s another matter. Onto Coriolanus. The first thing we hear/read in this play is a citizen. First Citizen From the outset, the people take the stage and state their demands. They are mad as heck and not going to take it anymore. There is the sticky issue of First Citizen and the chorus of other citizens. Is First Citizen just another “leader” silencing the people? As we eventually get more voices, I would argue not. This is just a staged way to show that the people are fed up with the political system and are willing to die for change. There are moments in earlier plays were the common people are moved to action against this or that person, but this is the first instance in Shakespeare where there is a clear and open revolt against the system from the outset. We can create the parallel to the contemporary political landscape in the US. There is, from time to time, greater than average resentment of the political status quo. The 2016 election has shown such a resurgence in resentment. There was a vocal majority on the right who rejected the typical Republican politicians (Bush, Cruz, Rubio) and fled to the outsider, the shaker-upper, the Donald. Meanwhile, on the left, a vocal minority fled from Clinton (the poster child for the status quo) and went to Bernie Sanders (the poster child for the failed Occupy Wall Street movement.) On either side, these two men speak for those who, like the citizens in Coriolanus would rather die than famish, which in the modern context means accept the risk of uncertainty than continue with what they have. No one, leading up to the 2016 election, knew what kind of president Donald Trump would be, but as long as he is not the current establishment, he must be the better alternative. Who do the Roman citizens blame for their strife? Who is the current establishment? According to the First Citizen, Caius Martius (who later becomes Coriolanus) is the “chief enemy of the people.” This is interesting because, although we do not know it at this point in the play, Martius is not a ruler, not part of the senate, nor a Tribune. He is a general, and thus his power does not extend beyond the command of soldiers in battle. To me, blaming Martius for the economic problems in Rome (the people not getting enough grain) would be like blaming Gen. Joseph Dunford for economic disparity in the United States. From the rest of the citizenry, Second Citizen rises to challenge First Citizen with this basic point. Why are you blaming Martius. Yes, he is maybe too proud, too boastful, but he has earned it. He has served his country well. His nature does not equal the faults First Citizen accuses him of. Menenius, the kind wise man, arrives and through an allegory, comes close to persuading the people to calm down. But wouldn’t you know it? Martius arrives. And like certain politicians, whenever he opens his mouth, some people are going to be offended. After Menenius offers the people kind words, Martius says: He that will give good words to thee will flatter And when he is told of the people’s complaint about not getting enough corn, he says: They'll sit by the fire, and presume to know While Menenius would present them with rose-tinted lenses, Martius speaks the truth, even if it insults them. We don’t get a proper resolution to this scene. Others rush in to inform us that the Volscians (an Italian group that warred against Rome in the early days) are attacking. Martius is the man for this particular job, and the citizens, knowing this, remain quiet. The opening to Coriolanus highlights a question regarding the mentality of the common people. What do we really care about? Is it enough for our voices to be heard? The citizens do not demand to be heard again for the remainder of the scene. Can we infer that they are placated? They are ordered to go home twice, once by Martius and once by a senator. The first order is cut off by the entrance of the messenger, Martius rebuffs the second order. But the citizenry in Julius Caesar would scatter immediately after the first order, these citizens remain. Shakespeare does not use silence sparingly. Their large presence on stage punctuates the talk of war, until, in the end, they leave following Martius. Actions speak louder than words. Until campaign season.

Shakespeare takes the idea of the Roman “campaign” and, in a similar way, transforms it into a far more staged act than it was in Rome itself. After his victory in Corioli, Martius was rewarded by having his proud traditional Roman name replaced by one that sounds like a prostate problem (there, I got the butt pun in). His next move is to “run” for consul, the highest elected official in Rome. Roman elections as Shakespeare presents them in this play were not accurate, intentionally I believe. Shakespeare constantly infused modern England into his plays. Sometimes this was explicit, such as the society in Measure for Measure, and sometimes slightly less so, such as the relations in Hamlet between Claudius, Hamlet Sr., and Gertrude (mirroring Henry VIII’s relationship with his dead brother and Katherine of Aragon.) In Coriolanus, Shakespeare sets up a Rome in which a candidate must (literally) obtain the voices of the people in order to be ratified as consul. In reality, at this point in history, the people had no voice in the matter. Consul was not even called Consul but Praetor, but that’s a minor point. By making it so that Coriolanus needs to obtain the people’s voices, Shakespeare (1) sets up the dramatic scene that occupies the centrepiece of the play, and (2) brings Roman society more in line with the contemporary English culture. So Coriolanus must beg for the people’s voice so that he may be consul, which he is loath to do. But after some urging from his mother (a refrain for this play) he concedes: Well, I must do't: Meanwhile his rivals, Brutus and Sicinius, are plotting against him. These two hate Coriolanus because he is too proud, and he made fun of them when they were chosen as Tribunes. Not the greatest motivations for villainy: whatever success these two have as dramatic characters seems to rest on an audience’s ability to say “oh yeah, they’re throwbacks to Cassius and Brutus from Julius Caesar.” Brutus and Sicinius use the ever popular tactic in modern politics to destroy Coriolanus: create some half-truths about how he is corrupt and a liar in order to rile up the people, who will take to their old Roman version of Twitter at which point the half-truths become accepted as fact. “Yes, of course every single Muslim will be deported from the US as soon as Trump takes office.” “Yes, of course Hillary Clinton deleted her emails as a deliberate middle finger to the people, so that she may hide her evil intents.” Lines like this is how Brutus and Sicinius will destroy Coriolanus. At one point, they even instruct the people to repeat whatever line they give them, regardless of context. For if campaigns are a staged act, he who speaks with more authority (louder) will win. Where this play starts to fall apart for me is just how well Brutus and Sicinius’ plan works. It is the same flaw with Othello: Iago plots to make Othello jealous and thus ruin him, and it happens really easily. Maybe I’m being too harsh. Theatre (particularly at this time) was not about realism. As much as Shakespeare infused his characters with any form of psyche, the slow devolution of a man would not become popular in theatre until the 20th century. This is just one reason why Hamlet rises above the rest. Othello and Coriolanus belong to the 17th century, where the excitement lay in seeing a proud figure walk into the snare set for them, seeing their hamartia (fatal flaw) catch them. This is what Coriolanus does. Whereas initially Coriolanus was able to win the people’s voices (in a scene that played much like the opening scene) after Brutus and Sicinius lay their traps, the people turn against Coriolanus. Brutus and Sicinius claim that Coriolanus wants to take all power unto himself and become a tyrant and therefore is a traitor (again, a callback to Julius Caesar.) What is most interesting about this pivotal moment in the play is that we no longer get First Citizen or Second Citizen, they are, like most other mobs, mere echoes with lines such as: To the rock, to the rock with him (III.iii) And It shall be so, it shall be so; let him away: All that matters is that they are loud and repeat what their betters (Brutus and Sicinius) said. All this culminates in Coriolanus becoming very angry, which only validates their concerns and therefore he is banished from Rome. Are the people that weak-willed? Is the writing too contrived? Any scan of a major politician’s Twitter account will reveal that even the most mundane tweet has numerous retweets. Recently, Trump’s posts are retweeted well over 1000 times, even ones that don’t really say anything. I don’t want to read too much into the average Twitter user’s mentality, but a retweet is our modern example of the citizens echoing Brutus and Sicinius. In our current age of retweets and memes, we are losing the desire to express any individual thought. We are melding into the citizenry, rather than the distinct voices of First and Second Citizen. It is not until the banished Coriolanus returns with an army at his back to conquer Rome that we see the distinct citizen voices again, this time to play the blame game and string up their once leaders, Brutus and Sicinius. I have glossed over most of the play. Coriolanus is not your typical hero with a fatal flaw. He is rarely sympathetic and he is not likable. His death isn’t even a result of a fatal flaw. He tries to place himself in a subservient position to his new friend, Aufidius, leader of the Volscians. Aufidius does exactly what Brutus and Sicinius did, and we get a repeat of the earlier scene, but instead of banishment, Coriolanus is killed. The end.

What are we supposed to take away from this play? How easily we are manipulated? How men who do not follow society’s customs, who try to rise too high must be cut down? Did the citizens (either Roman or Volscians) believe that Coriolanus would become a tyrant and restrict what little freedoms they had? Do we, in the lead-up to 2016, truly believe that if Trump were elected president, there would be a mass expulsion of people and a ridiculous wall built on the southern border? Is the massive outcry against both Coriolanus and Trump a gut reaction to the fear of the unknown? The same unknown that initially propelled Coriolanus and Trump to fame. The voice of the people – or elections – is a powerful tool and a dangerous one. We hand over certain aspects of our lives to one person (and whatever checks and balances modern societies have in place.) There are those, in Shakespeare’s time and today, who would try to gather as many voices as they could to bolster their voice. We cannot allow this to happen. Sometimes one person believes he can lead people when, in reality, he cannot. He may possess certain skills, but without the proper people skills, his leadership would be disastrous and destroy the state. We cannot allow this to happen. These are the two sides to Coriolanus, either one revealed whether you view Coriolanus as the hero or the villain. That’s the thing about politics: it’s near impossible to truly believe two opposing narratives at the same time. Shakespeare tries to present both at the same time, and it creates an interesting play that relies far more on how you interpret it than what you see or read. Coriolanus is one of Shakespeare’s play of ideas (to steal from a 20th century term), where the characters are not nearly as important as the ideas behind them. The problem is that Shakespeare’s mastery lies in his characters. So Coriolanus is an interesting play to play with. I zeroed in on one aspect. but there are other interesting aspects, such as the role of women as shown in Coriolanus. It is certainly a more cerebral work: one that won't capture the audience as well as the sublime Romeo and Juliet, the witty Twelfth Night, or the spectacle of Macbeth. Still, if you have the patience to read this play several times, and that does require effort, it yields some rewarding thoughts.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed