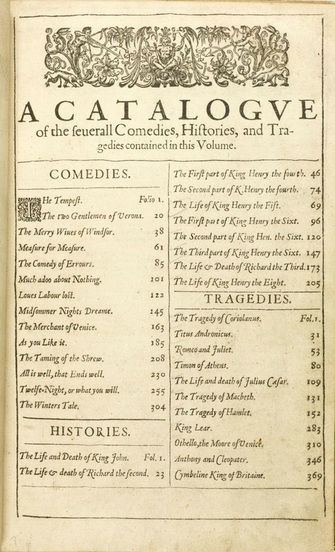

Twelfth Night, or What You Will is Shakespeare’s last “pure comedy”. Following this play, first performed in either late 1601, or more likely 1602, the plays that fall in the comedy category are the three problem plays (Troilus and Cressida, All’s Well That Ends Well, Measure For Measure) and the Romances (Pericles, Winter’s Tale, Tempest). Incidentally, Troilus and Cressida could very well have been written before Twelfth Night. There is a debate about this (isn’t there always) but since Feste references Troilus and Cressida in III.i I choose to believe that Twelfth Night followed closely after Troilus and Cressida. To play Devil’s Advocate however, Shakespeare also references the characters of Troilus and Cressida in Merchant of Venice (V.i), a play certainly written before Troilus and Cressida: all this goes to show how fickle these debates on dates truly are. And yet, the implication in believing that Twelfth Night was written after Troilus and Cressida is that Twelfth Night becomes placed in the centre of the problem plays. Is it a problem play? It is not often thought so. But it is agreed that there is a distinction between Twelfth Night and the other “pure comedies”. Twelfth Night is most often compared to As You Like It due to similarities that I will touch upon. As You Like It was written shortly before Twelfth Night, but there is a key factor separating the two plays, and his name is Hamlet. Shakespeare’s pre-Hamlet career was marked by histories and “pure comedies”: there were only three tragedies. Post-Hamlet sees tragedies, Romances, and problem plays – with Twelfth Night lingering in a crowd that it does not seem to belong. So while Twelfth Night reaches for earlier comedies like Comedy of Errors, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, or most notably As You Like It, it cannot get past the sheer darkness that is Hamlet. As with Hamlet, Twelfth Night is preoccupied with death. We first hear about Olivia as she is in an Hamlet-like state of mourning for a dead father and brother. Viola and Sebastian as well are in deep mourning for each other (as both think the other is dead until the end of the play). Pretense, and the fine line between being one person or another is a commonality shared between Hamlet and Viola. Madness of course, and its tragic consequences – albeit less tragic in Twelfth Night than in Hamlet – is another tie. The world is out of order in both plays – and with a very different tone than the chaos that hangs over Midsummer Night’s Dream. Thus, Twelfth Night is a marriage of As You Like It, and Hamlet. At the same time, I will argue that Twelfth Night is Shakespeare’s funniest play on paper. I believe that in classical theatre, tragedies (or histories) exist in the lines, comedies exist in the acting. This is true of Shakespeare. There is plenty of laughter to be had in Shakespeare’s comedies but often they require a good actor to convey the comedy. Take this example from Merchant of Venice, a speech by Launcelot the Clown. Certainly my conscience will serve me to run from Reading this monologue or listening to it probably did not make you laugh, but throw in some visual gags and you’ll get a chuckle or two.

Because who doesn't love a good awkward sex joke. But you see from this that the comedy of Twelfth Night is more embedded in the words themselves than previous comedies. In high school, we tend to teach the tragedies because (among many reasons) they resonate better on paper as opposed to the comedies which lose a lot when not seen. When schools do teach comedies, Twelfth Night is a safe bet for this reason. Just another factor that pushes Twelfth Night away from its fellow comedies and into the world of tragedy. Given this, can we say that Twelfth Night is a tragicomedy? Tragicomedies were becoming more popular in English theatre and Shakespeare would turn explicitly to them at the end of his career. However, unlike tragicomedies, which blend tragedy and comedy into a unified experience, Twelfth Night presents us with a struggle between the two forces. For example Clown  When Claudius accuses Hamlet of mourning his father too much, Hamlet pushes him away for nothing shall clear the presence of death in Hamlet’s mind. Feste, reaching for Hamlet’s wit to battle Olivia, moves her (and the audience) to laughter. But Feste is not Theseus from Midsummer Night’s Dream, who with a word dispels the presence of death. Olivia laughs but a moment later she orders her veil before she meets Viola: she cannot throw off her mourning – that is until she falls in love with Viola. A constant struggle exists in Olivia between mourning and merriment. Perhaps the best way to view the marriage of As You Like It and Hamlet, and the greatest way to view most of the key issues of interest in this play, is through the central character Viola/Cesario: central to the action despite the fact that she only speaks 12.5% of the lines in the play. Viola ends up on the strange shores of Illyria (a made-up country somewhere in the Adriatic) after she and her twin brother are shipwrecked. She thinks her brother is dead and we first encounter her in a state of mourning: And what should I do in Illyria? When she is told about Olivia she immediately recognizes herself in Olivia (and of course Viola is literally in Olivia, but I will get back to that) and longs to be with her. The captain informs her that Olivia will admit no one, so instead Viola has him present her in men’s clothing to the Count Orsino, telling the Count that she is a eunuch named Cesario. Viola/Cesario is often compared to Rosalind from As You Like It: they are both women who disguise themselves as men in order to blend into a foreign place, and once there both help a love-sick man attain the love of the woman he desires. The grand difference between the two is that Rosalind helps Orlando attain the love of Rosalind (herself), whereas Cesario helps Orsino to attain the love of Olivia. Meanwhile, Viola/Cesario loves Orsino – creating the problematic love triangle that is Twelfth Night.  But first: names. The first interesting point is Rosalind and Viola’s chosen pseudonyms. Rosalind chooses the name of Ganymede – kidnapped by Zeus and made the cup-bearer of the gods. Viola chooses the name Cesario, or little Caesar. Yet, in the realities of the plays, Rosalind is in complete control of her world and everyone in it, but Viola has no real power and is a relatively passive character, acting as a conduit for the action to flow through. So Rosalind is the Caesar of her world and Viola the Ganymede of hers, yet the names are as they are—to ask why they are not reversed is futile. Just an interesting point. The more relevant point about names is that if you are watching the play (and do not have a program in hand) you do not find out that the central character is named Viola until act V. Were you a woman, as the rest goes even, The fact that we do not know her real name until the end of the play puts us at a distance from Viola. Yes we know a fair bit about her before this point but since we only know her as Cesario it is hard to distinguish Viola from Cesario beyond their physical barriers (their genders). Rosalind/Ganymede had a partner to confide in: because she is with her cousin Celia, also in disguise, her character shifts between Rosalind and Ganymede. She is Rosalind with Celia, Ganymede with everyone else. Viola does not have this partner. The only other person who knows who she truly is is the sea captain and he disappears after his scene, and for whatever reason is arrested by Malvolio. Therefore, she is Cesario and only Cesario until the end. Yes, Viola slips through the cracks when Cesario speaks with Orsino, but not enough that we can truly distinguish the two. She is a mistress of disguise, second only to Hamlet. In this way she is Rosalind in her predicament: Hamlet in her distancing, and her tragedy. Furthermore, you really have to wonder why Shakespeare created the relationship in names between Viola and Olivia only to conceal Viola’s name. Is this meant to inspire reflection? Are you supposed to realize, after watching the play, that Cesario’s real name is so close to Olivia’s and this really strengthens the parallels drawn between the two characters throughout the play? I don’t know. There certainly are connections between Viola and Olivia. The first one, as I mentioned, is their shared losses. Of course Cesario never lost a brother and is not in mourning, Viola did. So this is a connection that Viola immediately recognizes but hides from Olivia. Cesario could have expressed to Olivia that he understands her pains, but Cesario is the dutiful servant to Orsino and thus was very careful to speak only within her text – that is say only what Orsino sent her to say: OLIVIA

“I am not what I am” is the truest statement we receive from Viola until she is unmasked at the end of the play. And it is a very Hamlet-like statement, for surely Hamlet is rarely who he is. Harold Bloom points to this statement in connection with Iago’s similar remark to Roderigo: “I am not what I am” (Othello I.i). But I do not believe that there is any real connection between the sinister Iago and Viola – just a recycling of lines. Going back to Rosalind in As You Like It: Rosalind fled the to the forest because she was threatened by the usurper, and she chose her male disguise because she thought that two women would not be safe in the forest. Viola does not find herself in this predicament. Viola is the daughter of a fairly wealthy man from Messaline, Sebastian, dead for some years. She arrives safely on the shores of a country ruled by a man who, as she informs us, her father was on good terms with. So why does she disguise herself? Why not just go to Orsino and explain the situation? The simple answer is – where is the comedy in that? But it is not until III.iv that we get a good insight to why Viola is not who she is, or why she continues her pretense. He named Sebastian: I my brother know  Viola maintains her disguise so she could keep her brother alive in herself. This prevents her from revealing herself to Orsino. This prevents her from confessing her love. This prevents her from escaping the awkward situation with Olivia. The need to keep Sebastian alive prevents her from living her own life. This is reminiscent of Hamlet. Hamlet cannot live his own life because he has sworn to abandon it in favour of his father’s cause: revenge. The difference between Viola and Hamlet is that Hamlet’s father is dead: Viola’s brother is not, and it is he alone that can unmask her at the end of the play. Sebastian is a relief for Viola at the end of the play, as he is a relief for the audience earlier on. Sebastian arrives on the scene at the start of Act II much in the same way Viola arrived at the start of Act I. He is in mourning for a dead sister and he goes to seek out Orsino. But while he is in his tragic state, a remotely educated audience knows that his arrival means the solution to the central issue of the love triangle. We know that Olivia will satisfy her love for Viola by getting Sebastian and Viola will be free to get Orsino. The only one who doesn’t get what he wants is Orsino, but he seems perfectly content with Viola. So while the dark moments hang over this play, we know by the start of Act II that all will be well and that we are indeed in a comedy. Sort of. Sebastian solves the love triangle, but what about the other threads of this play. It is about time we look at that. Shakespeare presents us with an interesting world in Illyria. Merchant of Venice, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and As You Like It all deal with two worlds – the “civilized worlds” (Venice, Athens, the French court respectively) and what Northrop Frye termed the “green world” (Belmont, the forest, the forest of Arden respectively). Two Gentlemen of Verona, Merry Wives of Windsor, and The Winter’s Tale also display this contrast. The way Frye describes the “green world” as working is: The action of the comedy begins in a world represented as a normal world, moves into the green world, goes into a metamorphosis there in which the comic resolution is achieved, and returns to the normal world. (Anatomy of Criticism) Do we get this in Twelfth Night? The play seems to take place in a unified location – Illyria. There are people who move from the “normal world” into Illyria: Viola, Sebastian, Sir Andrew Aguecheek, and Antonio, but we do not see them before they come to Illyria, so there is no transition there. And yet, Illyria itself is a divided place. The action of the play takes place in Orsino’s court or Olivia’s house. There are only two characters – Viola and Feste – who are able to move between the two houses. There are scenes that happen on the street, and two scenes on the sea coast, but only Viola and Feste breech the doors of both houses. Sir Toby, Sir Andrew, Maria, and Malvolio have no place in Orsino’s palace, just as Orsino or his nobles have no place in Olivia’s house. Feste explains his ability to travel between the two houses when he says: “Foolery, sir, does walk about the orb like the sun, it shines every where” (III.i). What he is alluding to is the common notion that the character of the Fool is an outsider, the basis of his comedy is that he is able to provide commentary into a world in which he doesn’t belong. Viola is also an outsider, in a more literal sense. But she is able to travel between the two houses due to her disguise. The fact that she is not who she is allows her to be whoever she wants to be, and this gives her access to both houses. Unlike Andrew Aguecheek who is only who he is and is tied to Sir Toby. Even Sebastian, another physical outsider, says he will go to Orsino but never seems to make it there, and is trapped in Olivia’s world. But do the two houses constitute two worlds? Is one, as Frye would say, a normal world and one a “green world”? If anything, Orsino’s court is the civilized world, and Olivia’s house the “green world.” Melancholy holds sway in Orsino’s court. Even the Fool is subdued. The song Feste sings for Orsino is Ben Kingsley, who would have thought? This is the tone of Orsino’s court: nothing loud or excited happens there. The famous opening line of the play “if music be the food of love, play on” seems to set his court up as a place of music and merriment, but Orsino quickly dispels this and the court just becomes mellow. Olivia’s house on the other hand is a place of pure chaos. While Olivia tries to live in a state of mourning, Sir Toby and Sir Andrew turn her house into an Alehouse, drinking and singing until all hours of the morning. Feste’s songs are livelier, or at least happier – Sir Toby’s jests are outrageous and even the steward, Malvolio, becomes a madman. On the one hand, Olivia’s house is meant to be a place of harmless fun – like Puck’s jests, Sir Toby is cautious to play pranks that don’t have any real consequences. Even when urging a fight between Cesario and Andrew Aguecheek, Sir Toby and his accomplice Fabian are always mindful of the law, and push the scene towards harmless fun. SIR TOBY BELCH In this sense, Olivia’s house is much like the forest in Midsummer Night’s Dream – Malvolio is transformed into an ass, and Cesario and Andrew Aguecheek are set against each other as Lysander and Demetrius were. However, Sir Toby is not Puck and there is no magic involved – so unlike the events in the forest, the events in Twelfth Night do not become a dream: they have real consequences. The fight between Cesario and Andrew, initially harmless, becomes out of control when Andrew and Sir Toby confuse Sebastian with Cesario. Cesario, as Sir Toby rightly judges, is not prepared to fight and thus there is no harm – but Sebastian seems quick to anger and draws his sword against his two attackers the first chance he gets. He wounds both Sir Toby and Andrew – turning the harmless fun into near death. And yet, no one is actually punished for this act. The incident is quickly taken over by the revelation of Viola’s identity and we forget that Sir Toby is hurt, or that the doctor is drunk in the morning. We kind of assume that everything on that end will work out fine. The other incident however, the one with Malvolio, has darker consequences. Malvolio was humiliated and imprisoned because of Toby’s harmless fun. His final words, hanging so close to the end of the play, are: "I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you" (V.i). We never find out what happens with this. Olivia sends someone to fetch him to smooth the matter, but will it be? If we were to have the hypothetical Act VI of this play, would we have a revenge tragedy on our hands? Olivia’s house is a “green world” as Frye defines it because Viola undergoes “a metamorphosis there in which the comic resolution is achieved, and returns to the normal world [Orsino's court]", but at the same time it is only because Sebastian was able to bring a resolution to the love triangle – Sir Toby’s acts have unresolved consequences, and there really is no metamorphosis. So as Malvolio’s curse silences the audience shortly after the joyous reunion of Viola and Sebastian, we see the struggle between comedy and tragedy – between As You Like It and Hamlet at its height. And we are unsure of how we should feel at the end. The final moment of the play is another Feste song, which only serves to add to the confusion and struggle of comedy and tragedy. I’d once again present Ben Kingsley, but the director of that version works against the text of the final song in order to present Twelfth Night as a neatly-wrapped up comedy. So here is Alfred Deller: The song is not really a joyous one. It is not as melancholy as the one Feste sings to Orsino, but it leaves us puzzled. He says “we’ll strive to please you every day” – but does he? (There are several other issues I could have explored in this play, but chose not to. One such issue is with Antonio, a seemingly minor character with a big impact; also one who really forces the question of sexuality in this play. Emma Smith, Oxford University professor, gives a great lecture on Twelfth Night, focusing in on the character of Antonio. It can be found here: I highly recommend it.)

1 Comment

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed